Gastrointestinal emergencies are common in general practice and the underlying problem may be overt or subtle. Appropriate effort and time should be given to stabilising a patient on presentation. For example, whilst mortality increases with a delay in a dog presenting with gastric dilatation volvulus (GDV) to the vet, it reduces with a longer time from presentation to surgery. Adequate analgesia using a pure mu agonist is often appropriate prior to surgery. A decision to operate is often based on clinical history and physical examination (eg abdominal palpation) but diagnostic imaging is often necessary. Persistent vomiting which is unresponsive to medical management can increase suspicion of intestinal obstruction and commonly results in hypokalaemia.

1. Consider serum electrolytes carefully

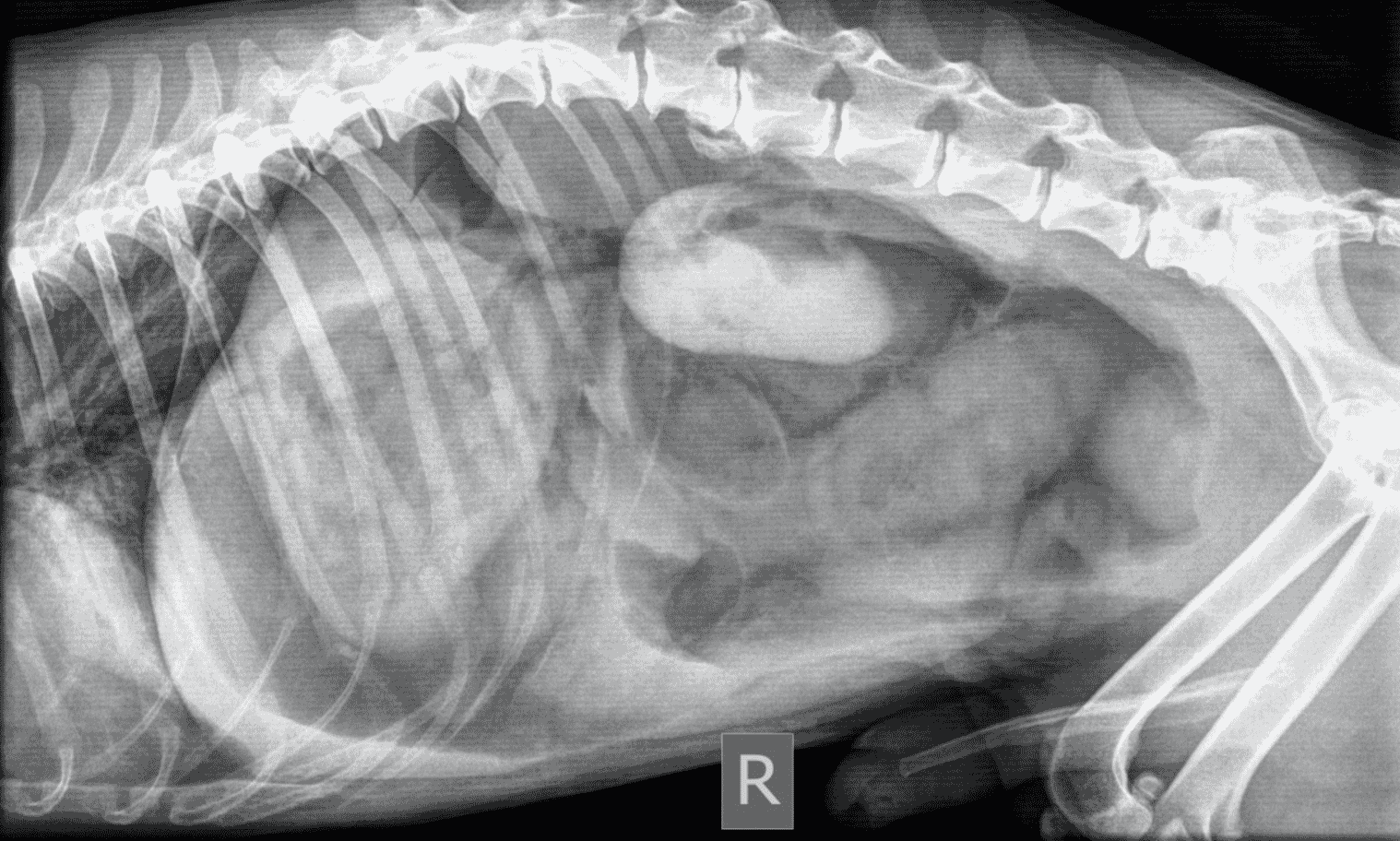

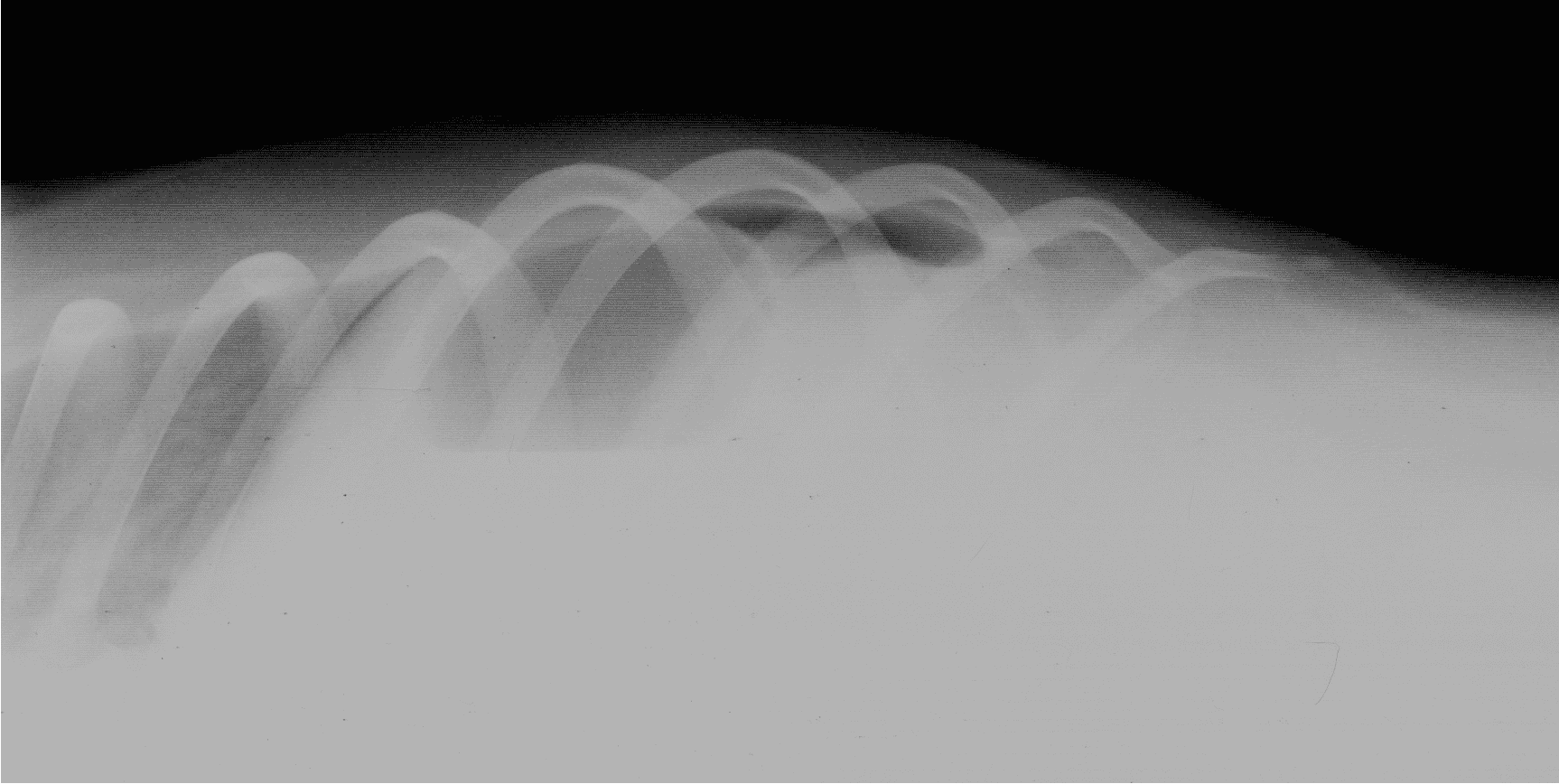

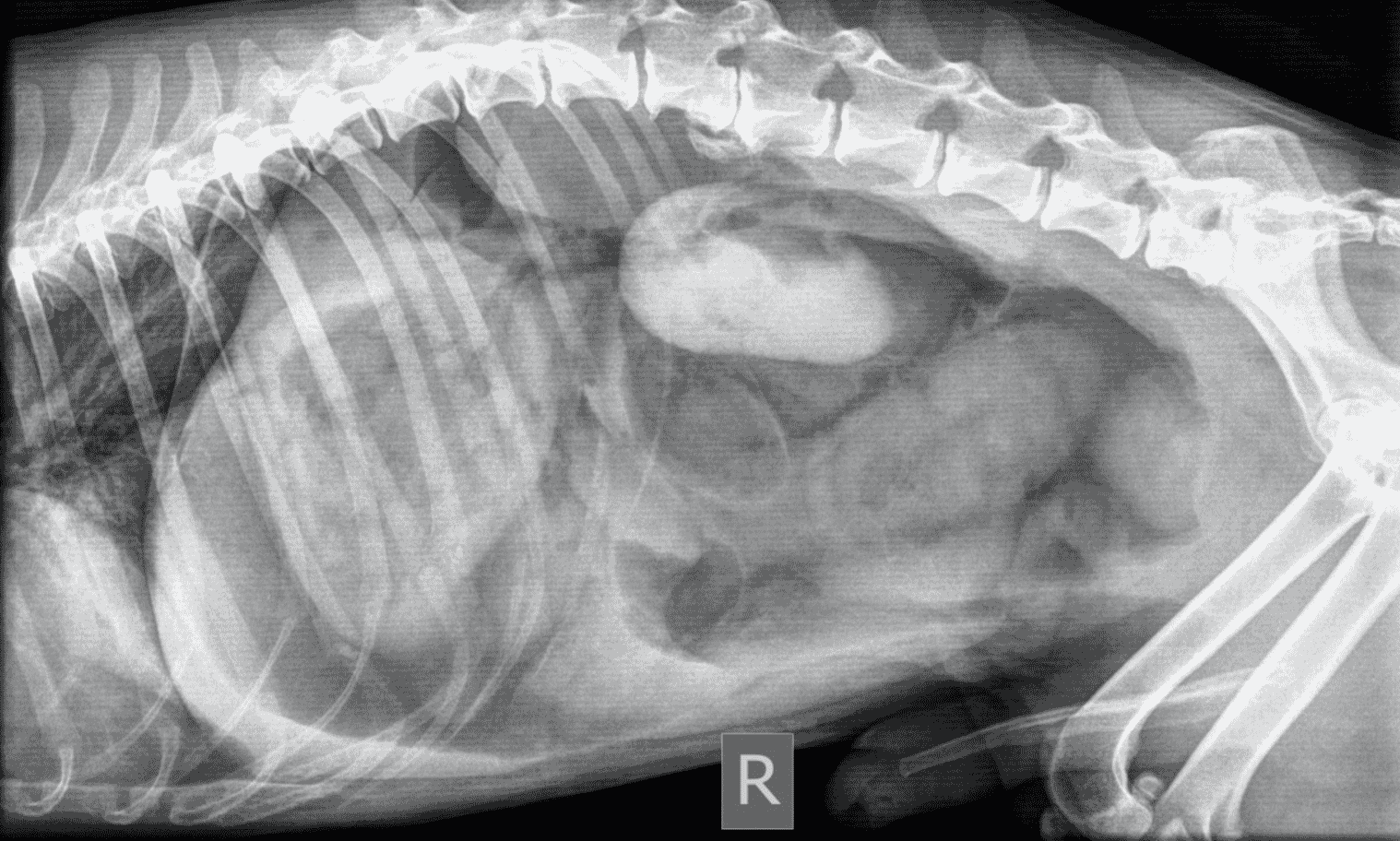

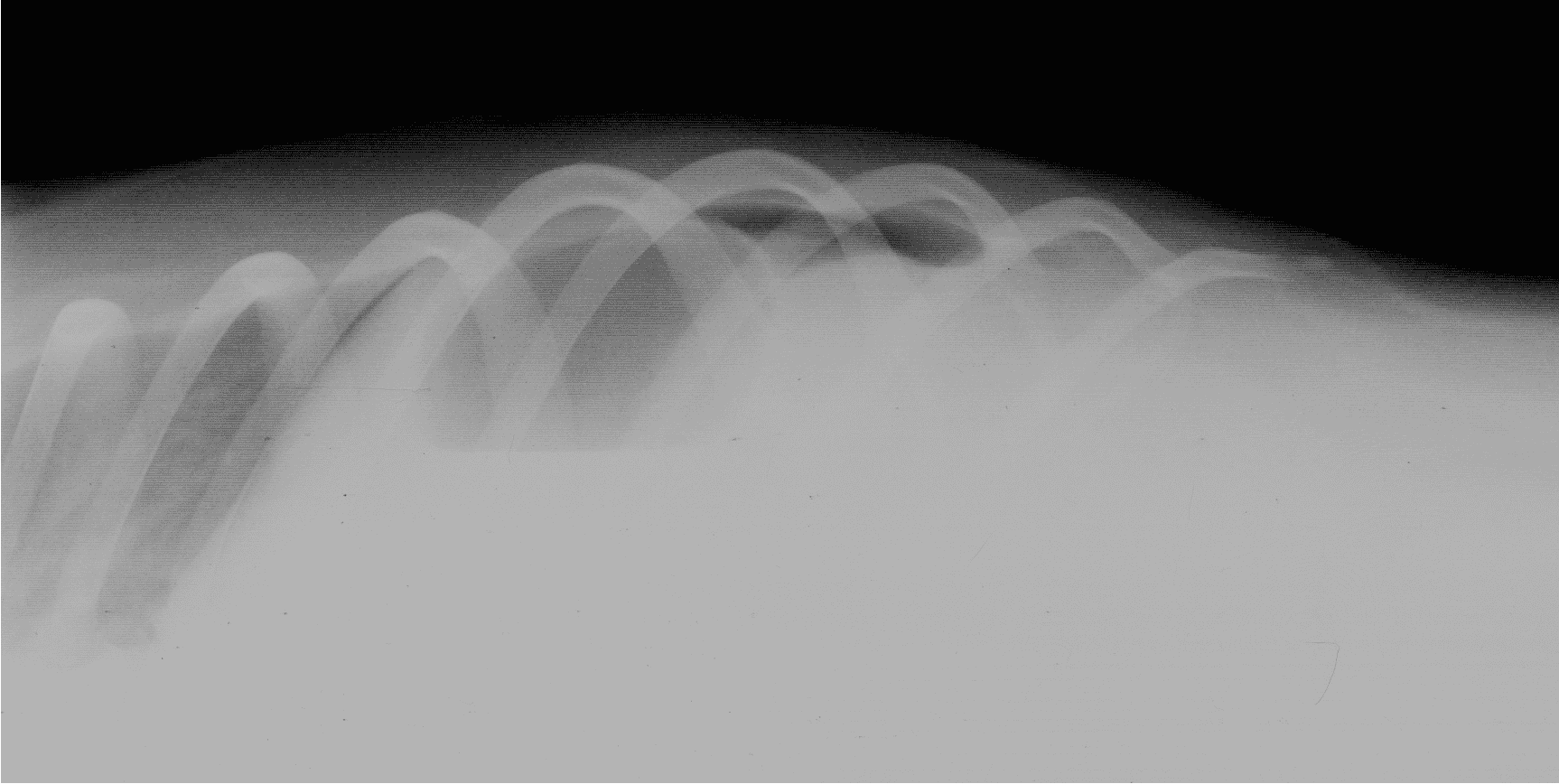

Proximal duodenal and gastric outflow obstruction can cause persistent vomiting with low serum Na, Cl and K; these electrolyte changes should be considered very suspicious even in the absence of imaging findings for obstruction. Abdominal radiographs should include orthogonal views (a right lateral and a ventro-dorsal or dorso-ventral image). Classic radiographic signs for surgical disease can include the “double bubble” for GDV ( Figure 1), two distinct populations of small intestine with obstruction (small and large diameter gut evident with, for example, intussusception, intestinal mass or foreign body; Figure 2) or free abdominal gas with a lack of serosal detail with septic peritonitis. Free abdominal gas can be very obvious ( Figure 3) but a more subtle pneumoperitoneum is best recognised using a horizontal beam radiograph with the patient in lateral recumbency ( Figure 4). Of course, a lack of radiographic changes does not fully exclude a gastrointestinal emergency and abdominal ultrasound can help to identify the problem or guide further diagnostics (eg abdominocentesis of free abdominal fluid). Septic peritonitis due to intestinal leakage will result in an effusion with cytological identification of neutrophils and/or bacteria. If intracellular bacteria can’t be definitively identified but there remains a concern for septic peritonitis, glucose and lactate assessment can be helpful.

2. Peritoneal fluid biochemistry

Free abdominal fluid glucose and lactate levels can be compared to serum levels, and if the lactate is higher and glucose lower in the abdominal fluid it can indicate bacterial anaerobic respiration. Fluid lactate more than 2mmol/l higher and fluid glucose more than 1.1mmol/l lower than serum should be considered very suspicious for septic peritonitis. If surgery is required, it is important to consider other procedures that might benefit the animal whilst anaesthetised. Biopsies of the intestine or liver may be warranted, and the placement of a feeding tube should always be considered, even if not performed.3. Feeding tubes should always be considered

Early enteral nutrition reduces hospitalisation time, facilitates intestinal healing and provides an alternate route for medication. Placing an oesophageal feeding tube is a relatively simple procedure which does not add a significant amount of time to the anaesthetic, is well tolerated by patients post-operatively (generally better than nasogastric tubes) and are useful if an animal has been anorexic prior to surgery or there is notable serosal inflammation or ileus recognised during surgery. Gastric tubes can help decompress the stomach or empty out copious fluid post-operatively and provide a route through which to thread an enterostomy tube (“J through G tube”) without the added complications that direct enterostomy tubes introduce. Animals should be offered food immediately following anaesthetic recovery. The resting energy requirement of a patient (RER) can be calculated and the animal started on a third of that amount per day if it has been inappetant, gradually increasing the amount each day to avoid refeeding syndrome.4. GDV: the pyloric antrum should be secured to the right body wall via incisional gastropexy

Following de-rotation of gastric volvulus, which is facilitated by emptying the stomach by orogastric tube or trocar decompression, the stomach is secured to the body wall. An incisional gastropexy of the pyloric antrum to the right body wall will result in appropriately strong adhesions with minimal risk of recurrence. Whilst other methods are described, they offer no benefit and increased complications. Left gastropexy is only indicated for oesophageal hiatal hernia. Partial gastrectomy and splenectomy are performed if indicated in the face of gastric necrosis or a compromised spleen. A mild haemabdomen concurrent with GDV is common due to avulsion of the short gastric arteries between the spleen and greater curvature of the stomach; this is also the reason why this region of the stomach is most often affected by ischaemic necrosis.5. Obstructions: learning to staple can help reduce the risk of complications

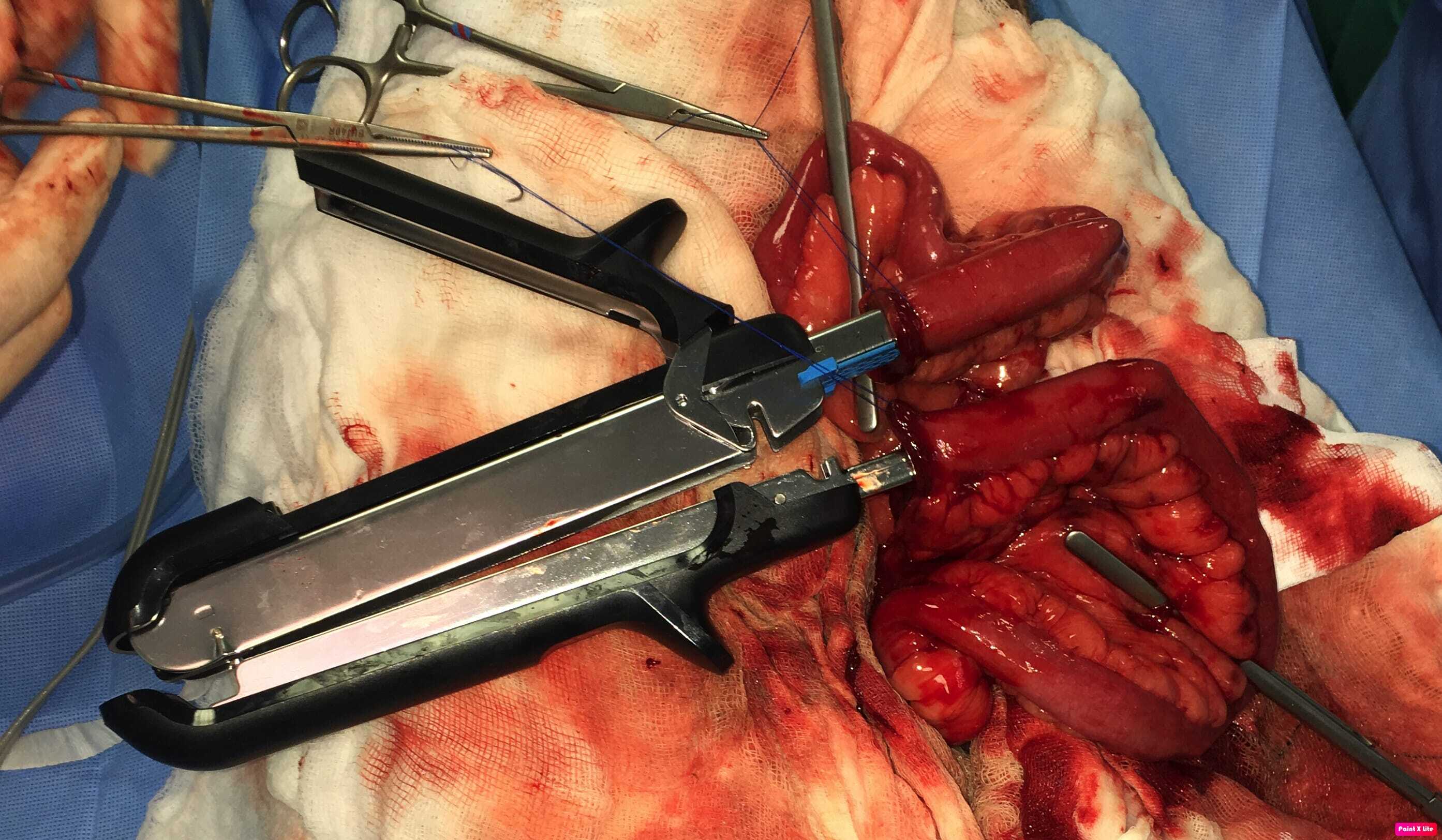

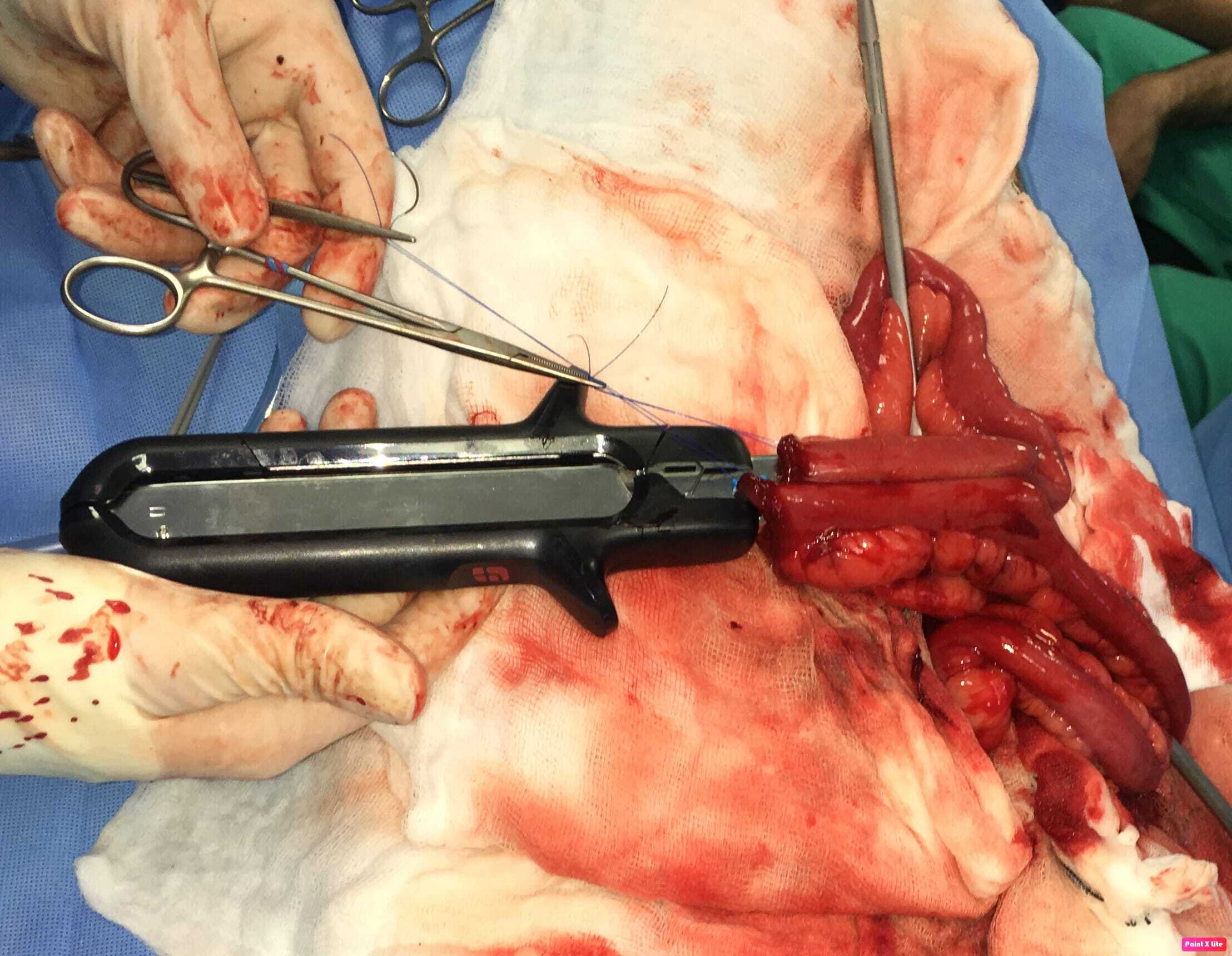

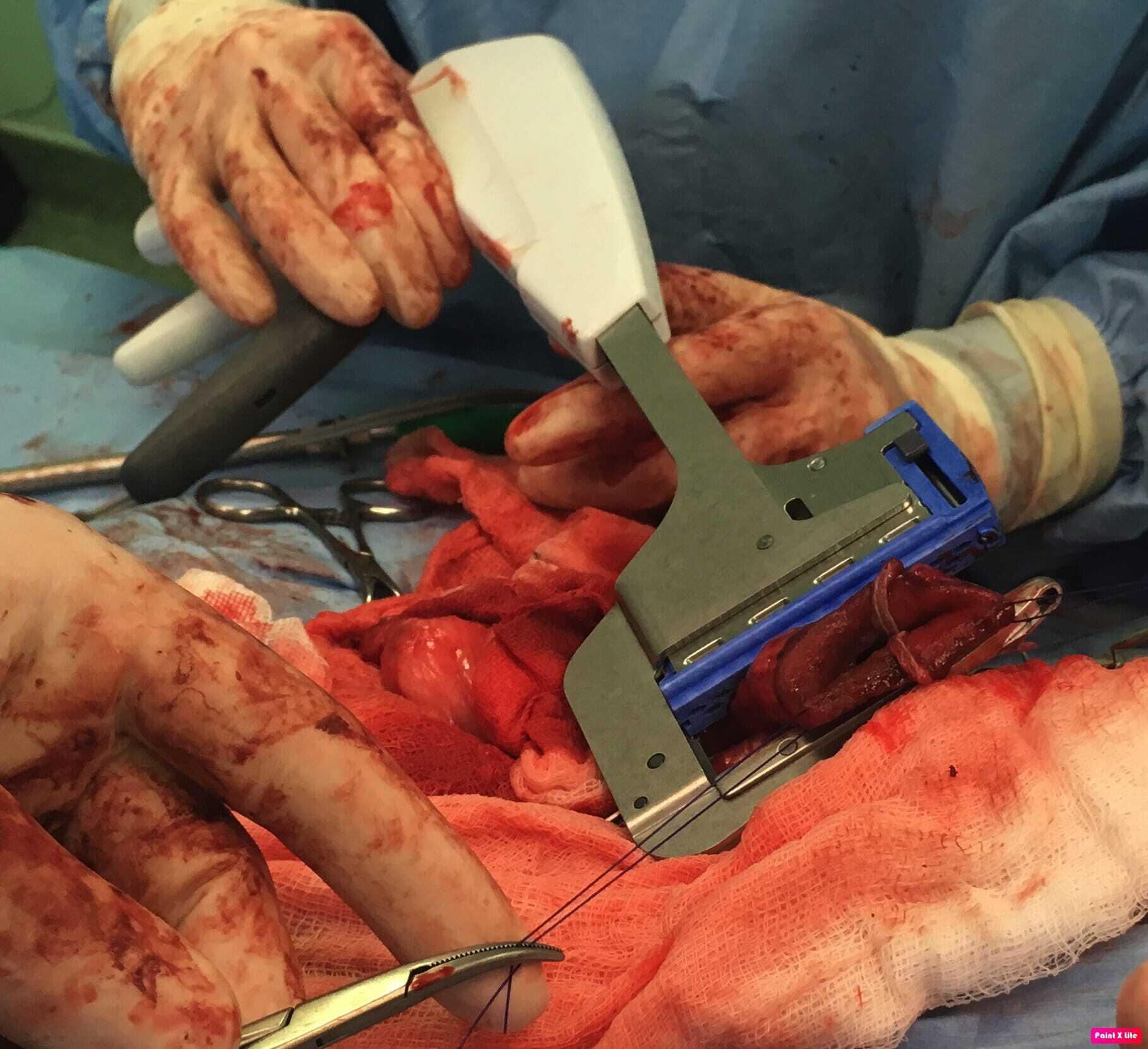

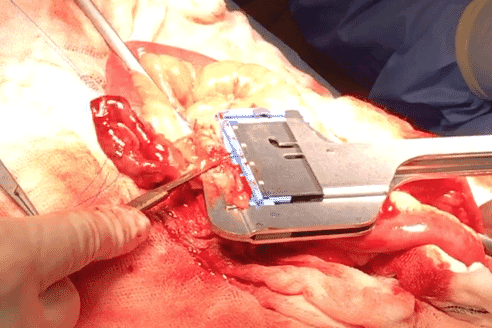

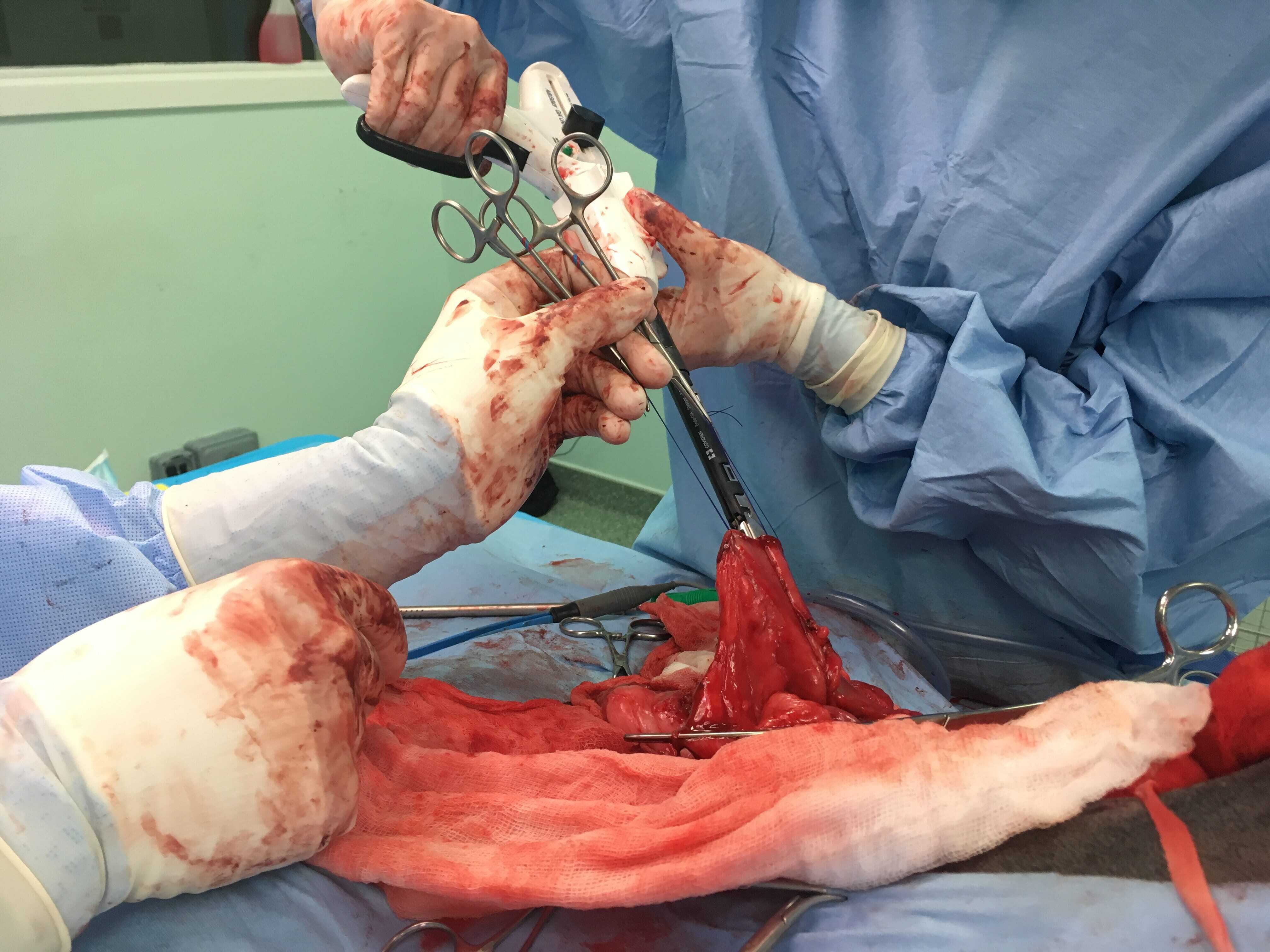

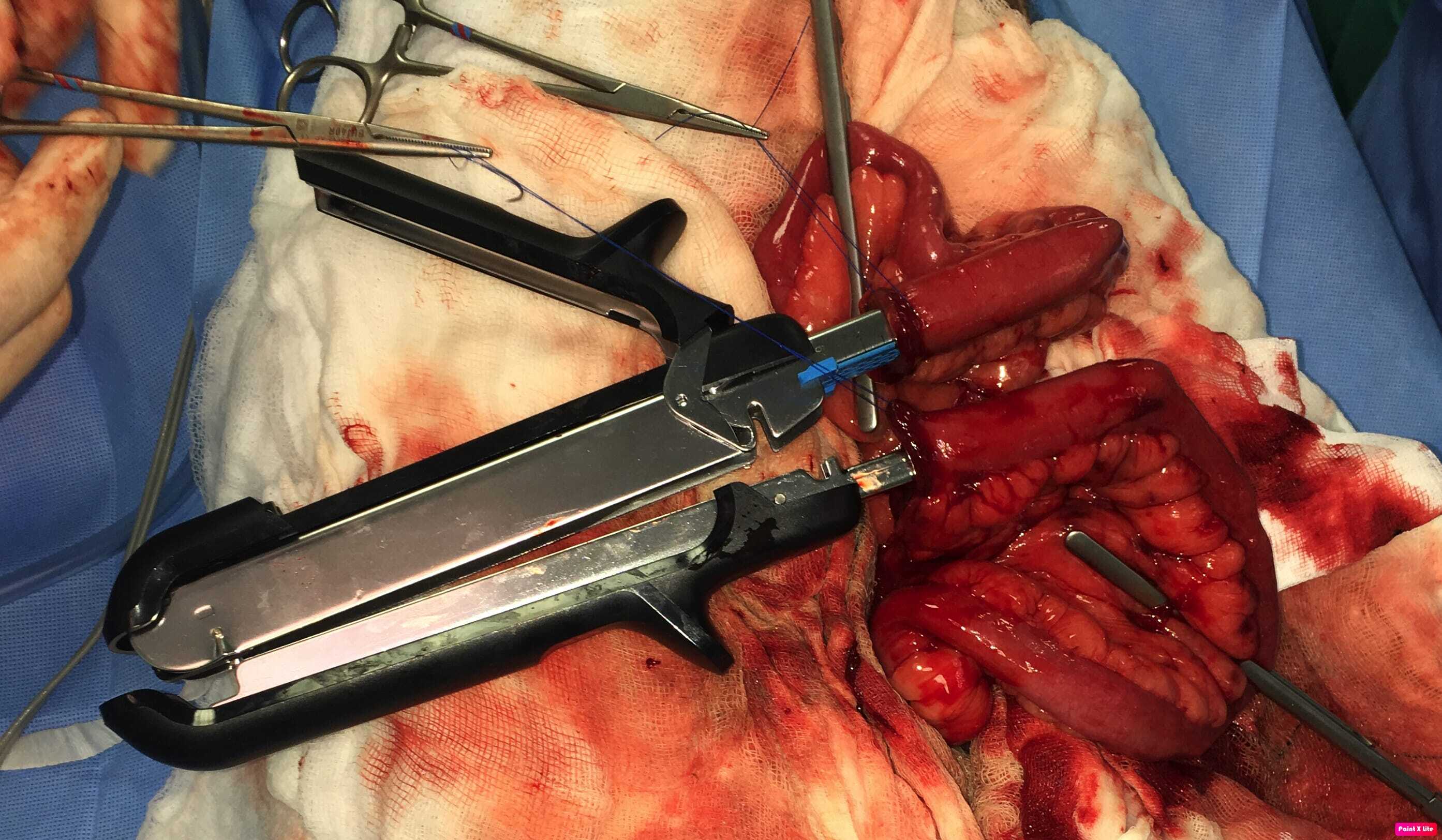

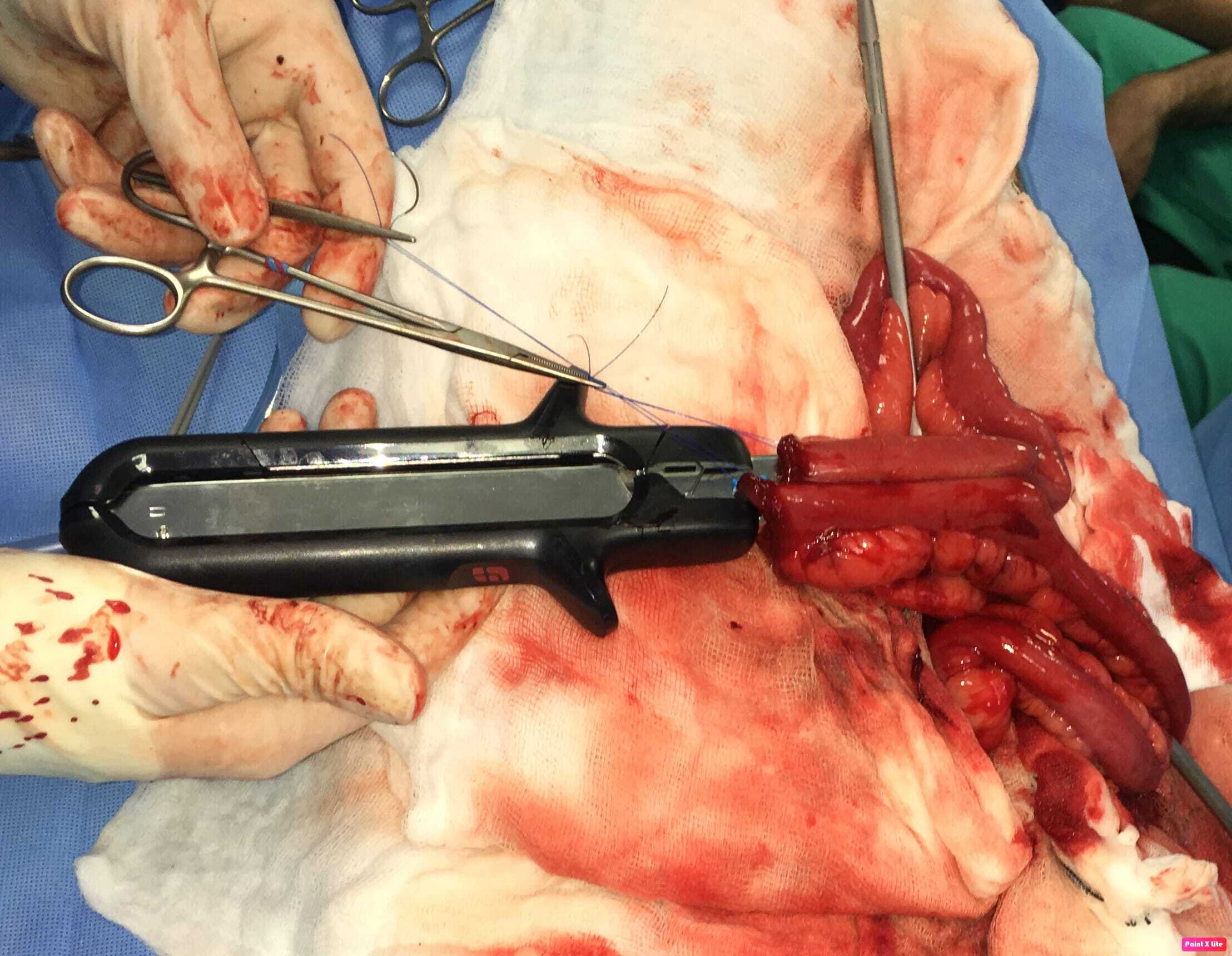

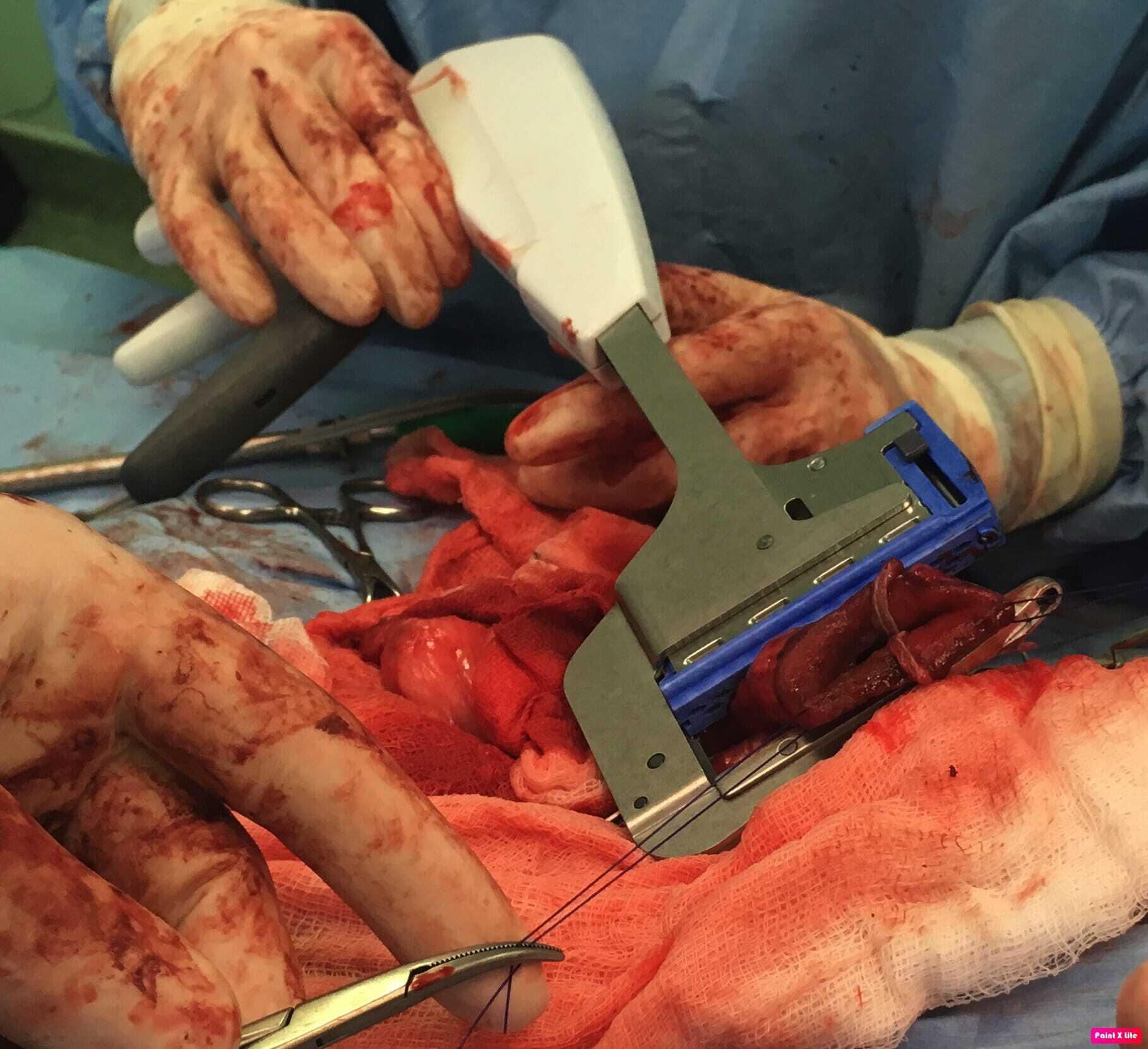

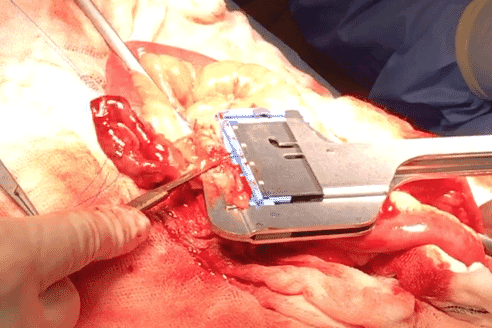

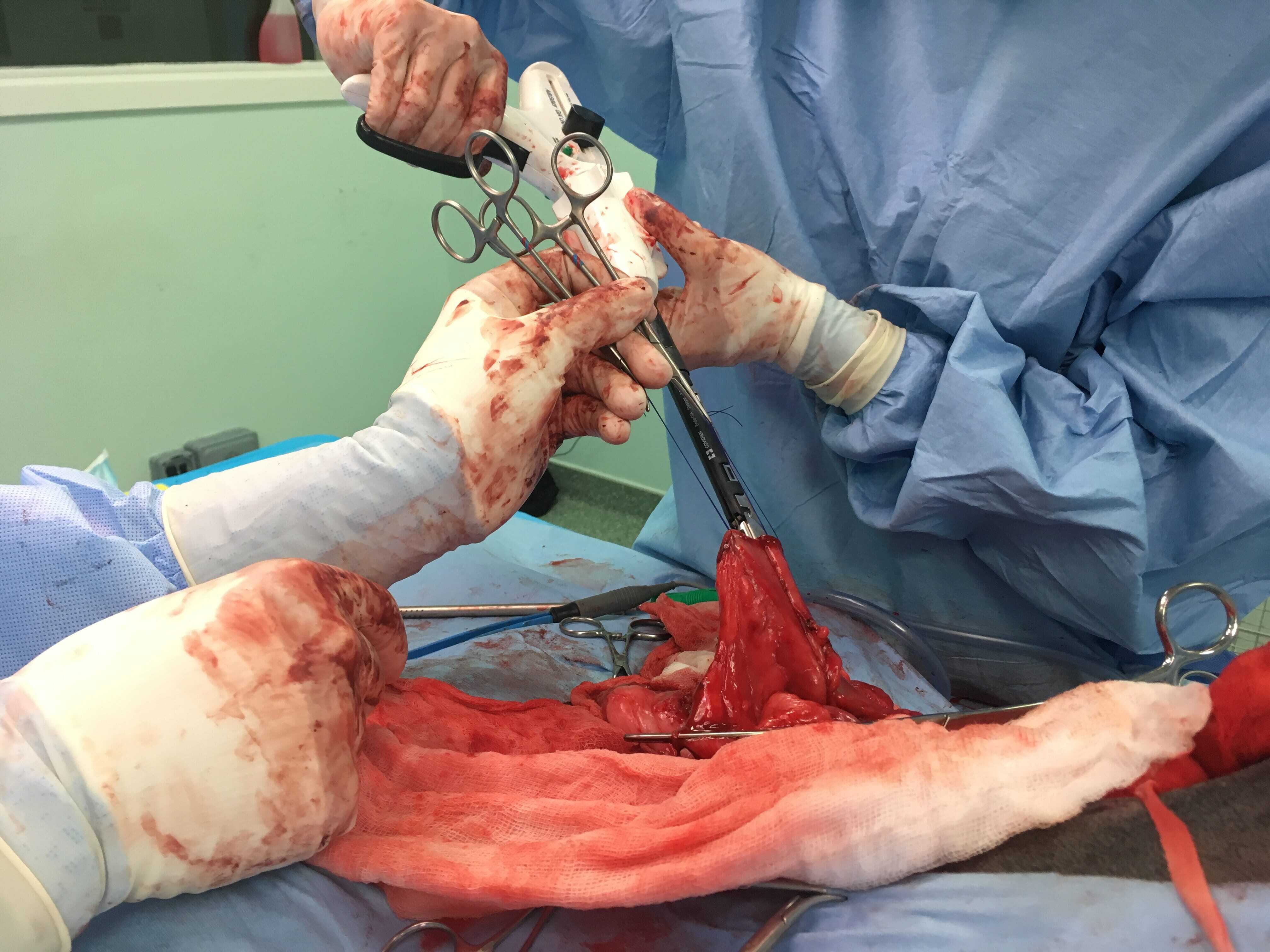

Intraluminal or extraluminal occlusion of the gastrointestinal tract is most often the result of neoplasia or foreign material. Oesophageal foreign bodies are best removed via endoscopy or fluoroscopy (approximately a 90 percent success rate). If they can be advanced into the stomach then surgical retrieval via gastrotomy rather than thoracotomy is less complex. Stay sutures are invaluable when performing gastrotomy to minimise the risk of spilling contents into the abdomen. Tissue viability of the intestines is typically assessed visually and by palpation (an experienced surgeon's assessment is 85 percent accurate), including identification of vessel pulses (thrombosed vessels are dark and do not blanch when compressed) and whether gut bleeds when incised. Sutured anastomosis following enterectomy is the most commonly performed method, using full-thickness single-layer simple interrupted or simple continuous suture patterns. The latter is preferable, as it is simpler, uses less material, is quicker and is more leak resistant. Surgical stapling devices can be used to create functional end-to-end anastomoses ( Box 1). Practitioners may be reluctant to use these devices based on lack of familiarity and cost but there are numerous advantages over traditional suturing, including considerably shorter surgical/anaesthesia time and a reduced risk of dehiscence in a septic abdomen. Overall, these reduce morbidity and cost. Box (1) Step-by-step guide to creating a functional end-to-end anastomosis using a linear stapling device and linear-cutter stapling device

Jon Hall, MA, VetMB, CertSAS, DipECVS, SFHEA, FRCVS, is a European and RCVS Recognised Specialist in Small Animal Surgery. Jon is head of Soft Tissue Surgery at Wear Referrals and a Professor of Small Animal Surgery at the University of Nottingham.