Dogs and cats can be uncooperative for the eye exam due to fear, anxiety or stress (FAS), especially with painful conditions. The ophthalmic exam requires magnified evaluation of the ocular structures with adjunctive tests such as intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement, fluorescein stain application and Schirmer tear test (STT) measurement. Patients can resist by closing their eyelids, extruding their third eyelids and moving their eyes, head and/or body. The examiner’s close hands and face proximity to the patient’s mouth during the exam increases bite risk. As such, various strategies need to be employed to achieve a safe eye exam for both the examiner and the patient, in a time window fitting the urgency of the presenting complaint.

By the end of this article, readers should be able to:

- Recognise eye exam technique strategies useful for uncooperative patients

- Recognise the utility and limitations of different restraint options for the eye exam

- Understand the impact of common sedatives on the eye exam and ocular tests

- Recognise abnormalities that suggest an urgent issue needing same-day evaluation

General tips for eye exams

In patients exhibiting FAS behaviour, gather as much information as possible from a distance before any manipulation or restraint is needed. Acclimatising the patient to your presence and equipment near their face is very important. You should aim to perform as much of the exam as possible before steps involving touching of the face and close face-to-face interactions. This includes:

- Observe from a distance: this may be wherever the patient is most relaxed (for example, the owner’s lap or their carrier). Consider completing the entire exam with the patient in this position

- Avoid direct eye contact: look for any gross abnormalities in comfort, conformation or symmetry (for example, blepharospasm)

- Prioritise exam steps: review any relevant pictures the client may have to help prioritise specific exam steps

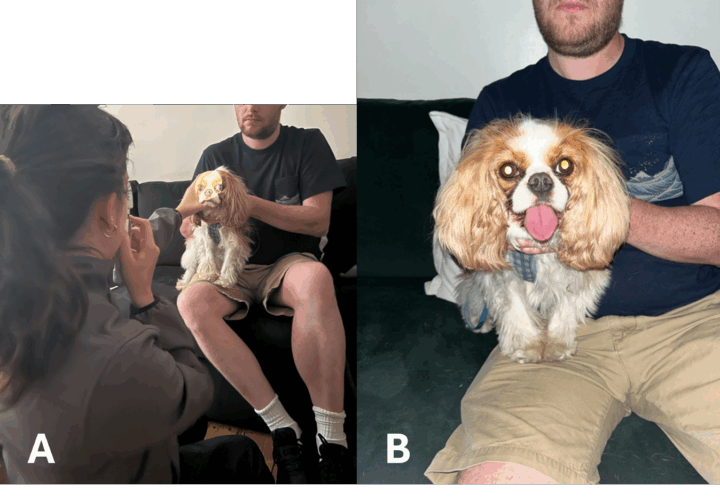

- Perform distant direct ophthalmoscopy: screening for opacities, pupil or tapetal reflectivity changes (Figure 1)

- Consider patient comfort: always dim equipment lights to the lowest level that permits examination. You should also provide frequent breaks and give treats for positive reinforcement

- Approach from an angle for the closer working distance steps, including ocular tests. Being directly in front of the patient is threatening, so start with the normal eye and then swap sides for each eye

- Test the menace response last: waving a hand into an eye is threatening

- Magnified exam:

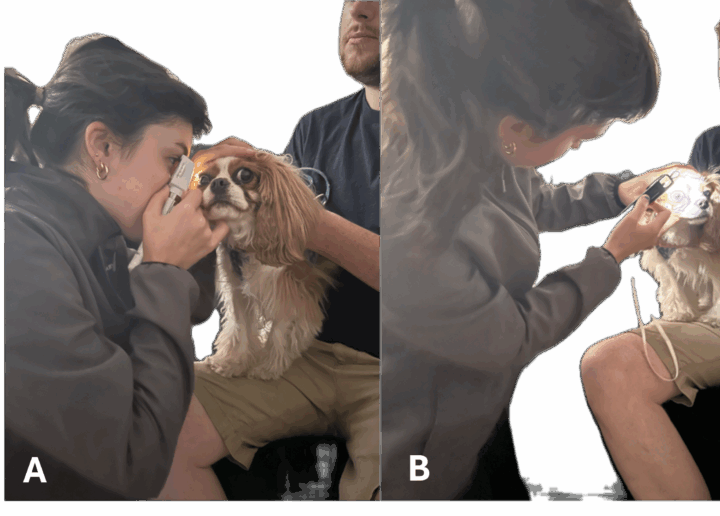

- Use the otoscope loupe (4x magnification, larger field of view, safer/less intimidating working distance) instead of the direct ophthalmoscope (15x magnification, extremely close face-to-face working distance, narrow field of view) for your magnified exam (Figure 2)

- Use an alternative magnification source (for example, a headband magnifier or loupes) for a safer working distance and improved sensitivity for detecting aqueous flare (Figure 3)

- Post-fluorescein application: don’t use eyewash to rinse the eye after fluorescein application; rather, wait 20 minutes for the tear film to dilute it out before checking for ulcers

- Consider your choice of equipment: choose indirect ophthalmoscopy (Figure 4A) over direct (Figure 4B) and panoptic ophthalmoscopy (Figure 4C) for a better working distance, ensuring no close face-to-face interaction and a quicker survey for the fundic exam. A referral may be needed.

When should I sedate versus when should I reschedule a patient

In a patient exhibiting high levels of FAS, options to complete the exam are:

- Sedation

- Rescheduling for another day with prescription of pre-visit pharmaceuticals

- Use of physical restraint devices (eg muzzles, towel wraps)

If any of the following acute abnormalities are identified via client photos, distant direct ophthalmoscopy or the distant exam, don’t reschedule to a later day as there is potentially serious vision- or globe-threatening disease requiring prompt diagnosis and treatment. These could include acute glaucoma, anterior lens luxation or an infected corneal ulcer.

- Blepharospasm

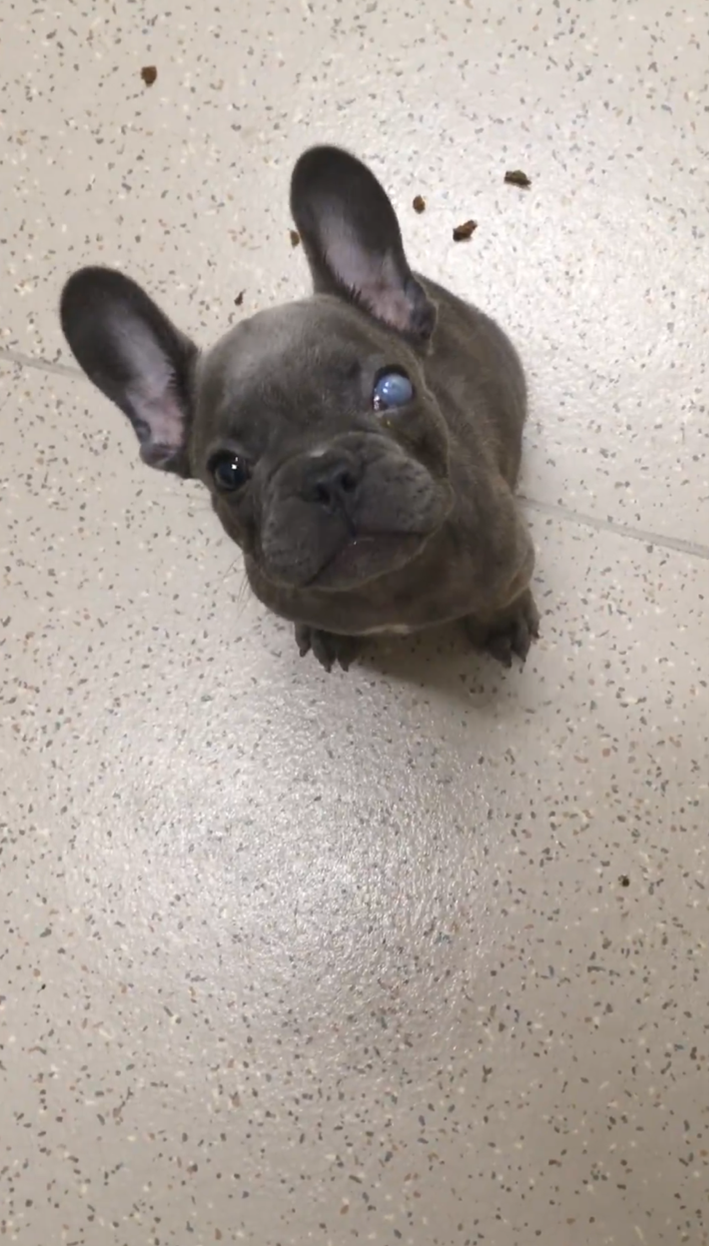

- Corneal opacification (Figure 5)

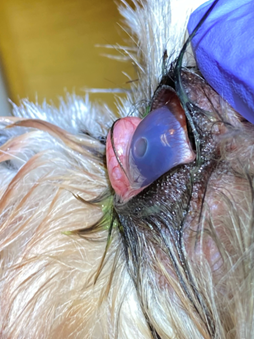

- Corneal topography changes, for example raised, protruding tissue or soft, melting appearance or corneal ulcer visible to the naked eye (Figure 6)

- Hyphaema or hypopyon

- Miotic or mydriatic pupil

- Vision loss

Consider emergency referral to an ophthalmologist if any of these abnormalities are found and the eye exam cannot be completed. Most non-painful chronic conditions can be rescheduled.

If there is concern for a fragile eye, such as a visible divot in the cornea (if a divot is present, at least 50 percent of the corneal stroma is lost), avoid any physical struggle otherwise the eye could rupture.

Tips for in-clinic physical restraint

- An experienced nurse or assistant should restrain – less is generally more

- Hold a hand under the chin to stabilise the head and lift the chin (Figure 7)

- Don’t force the patient to stay still – moving with them increases compliance

- Stabilise your hands against the patient when performing tests or examining at a close working distance. Note, in Figure 7, the operator’s right hand is stabilised against the left hand via a finger, which in turn is resting on the patient’s head, ensuring you move with them and reducing accidental trauma risk

- Although not cat-friendly, you can use a cat bag/towel wrap only for short, specific steps where the benefit outweighs the risk (for example, close face-to-face exam or IOP measurement)

- Avoid any neck pressure when restraining, including with towel wraps, as this can increase IOP

- Brachycephalic dog muzzles are problematic and need to be used with care. They can move around blocking access to the eye (Figures 8A and 8B). Mesh muzzles are also more likely to contact the cornea (Figure 8C) – which could rupture a fragile eye!

Common sedatives for ophthalmic exams

Pre-visit pharmaceuticals:

- Gabapentin and trazodone: no impact on ocular access or test results (Crowe et al., 2022; Shukla et al., 2020; Pelych et al., 2018)

- Acepromazine: may reduce ocular access, STT, pupil size, IOP. It is also less impactful than alpha-2 agonists (Aghababaei et al., 2021; Schroder et al., 2018; Micieli et al., 2018; Wolfran et al., 2022)

- Alpha-2 agonists: examples include dexmedetomidine oromucosal gel. These can reduce ocular access, STT, IOP and pupil size in dogs, while increasing pupil size in cats (Aghababaei et al., 2021; Schroder et al., 2018; Micieli et al., 2018; Wolfran et al., 2022). They have been found to be the most impactful (Aghababaei et al., 2021; Schroder et al., 2018; Micieli et al., 2018)

In-hospital sedation:

- Butorphanol: mild, clinically insignificant reduction in pupil size and STT in dogs. While in cats it causes mild, clinically insignificant increase in IOP and pupil size (Douet et al., 2018; Mohammadi and Yanmaz, 2023)

- Acepromazine and alpha-2 agonists: see pre-visit pharmaceuticals above

- Ketamine: may increase IOP, so you should avoid it if treating glaucoma or a fragile eye, but concurrent benzodiazepine administration can blunt IOP increase. It also may increase pupil size, but minimally impacts globe access or STT (Kovalcuka et al., 2013; Raušer et al., 2022a, 2022b)

For all sedatives, a dose-dependent effect on ocular variables should be expected. Most reduce STT and IOP, so for accuracy, these tests should be performed, if possible, prior to sedation. If STT values are still normal, ie more than 15mm/min for a dog, this is reliable, while if the IOP is still abnormal, ie more than 20 to 25mmHg in either species, this is reliable.

Sedated eye exam access

- Access can be challenging if ventral globe rotation, enophthalmos and third eyelid elevation occur (Figure 9)

- Use an eyelid speculum to hold the eyelids open

- After applying local anaesthetic (such as proxymetacaine), gently grasp the bulbar conjunctiva overlying the sclera with a small, toothed forceps to rotate the eye upwards

- A cotton-tipped applicator can be used to manipulate tissues (including the third eyelid), but should be avoided with potentially fragile eyes

Case study

An eight-year-old spayed female Australian Cattle Dog presented for acute onset blepharospasm and ocular discharge. The patient exhibited severe FAS behaviour and would not cooperate for an exam. All that can be appreciated is severe blepharospasm, ocular discharge and corneal opacification (Figure 10).

| Should you reschedule the patient for a later date with pre-visit pharmaceuticals, or sedate the patient for a complete ocular exam? |

Since the patient appears to be in pain and has evidence of corneal opacification, the patient was sedated. Under sedation, a full-thickness corneal laceration was identified, which was referred for emergency surgical repair by an ophthalmologist.

Conclusion

Examining uncooperative animals requires patience, gentle handling and strategic planning. Starting with a calm, observational approach, utilising appropriate restraint and sedation when necessary, and progressing gradually can make the process safer and more comfortable for both patient and examiner.