Congenital cardiac diseases present significant challenges in veterinary medicine. This series aims to provide an understanding of some of the most common congenital cardiac diseases found in dogs. It will briefly cover prevalence, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnostic findings, therapeutic options and prognostic considerations of five key canine congenital cardiac defects: pulmonic stenosis, atrial septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus, ventricular septal defects and subaortic stenosis.

Pulmonic stenosis

Prevalence

Pulmonic stenosis (PS) ranks among the most common congenital heart defects in dogs, accounting for approximately 31 to 34 percent of congenital heart diseases (Oliveira et al., 2011; Schrope, 2015). The prevalence can be notably higher within specific breeds, such as the English Bulldog and French Bulldog (Locatelli et al., 2013).

Pathophysiology

PS involves a narrowing of the pulmonary artery or the structures just above or below it. This impedes blood flow from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery, leading to increased pressure in the right ventricle and reduced blood flow to the lungs. The blood flow in the pulmonary artery becomes turbulent causing a left basilar systolic murmur. Soft murmurs in dogs with pulmonic stenosis are strongly indicative of mild lesions, whereas loud or palpable murmurs are strongly suggestive of severe stenosis (Caivano et al., 2018). Over time, these haemodynamic changes can result in right ventricular hypertrophy, right atrial dilation and, in severe cases, right-sided heart failure.

There are two main types of PS:

- Valvular – affecting the leaflets that are fused together

- Mixed – can show a valvular component with a narrowing that can be due to a hypoplastic pulmonic annulus or narrowing above or below the valve

In some breeds, such as the English Bulldog, the stenosis can be worsened by the presence of an abnormal coronary artery that wraps around the pulmonary artery (Buchanan, 1990).

The severity of pulmonary stenosis is classified by the pressure gradient (PG) across the valve, which is estimated using the Bernoulli equation

The severity of PS is classified by the pressure gradient (PG) across the valve, which is estimated using the Bernoulli equation (4 × velocity2) and the velocity of the blood across the pulmonic valve. PG can be measured with continuous wave (CW) spectral Doppler during echocardiography. PG values below 30mmHg are considered normal, while those between 30 and 50mmHg are consistent with mild stenosis, those between 50 and 80mmHg considered moderate and those above 80mmHg indicative of severe stenosis.

Clinical signs

Dogs with PS usually have a systolic left basilar murmur. Clinical signs of PS vary depending on the severity of the obstruction. Common manifestations include exercise intolerance and syncope, and in severe cases, signs of right-sided heart failure such as ascites and jugular distension and pulsation as well as muscle loss.

Diagnostic evaluation

Echocardiography is the best diagnostic tool to diagnose PS as it allows practitioners to evaluate the severity of the stenosis by measuring velocities across the valve, as well as any secondary changes such as right ventricular hypertrophy. Concomitant congenital diseases, such as tricuspid dysplasia, are possible and should be taken into consideration when creating future plans.

Electrocardiography (ECG) might be required to investigate ventricular arrhythmias and/or atrial fibrillation, which can be associated with PS – especially in severe cases. A deep S wave on ECG is also a common finding in dogs with right ventricular hypertrophy.

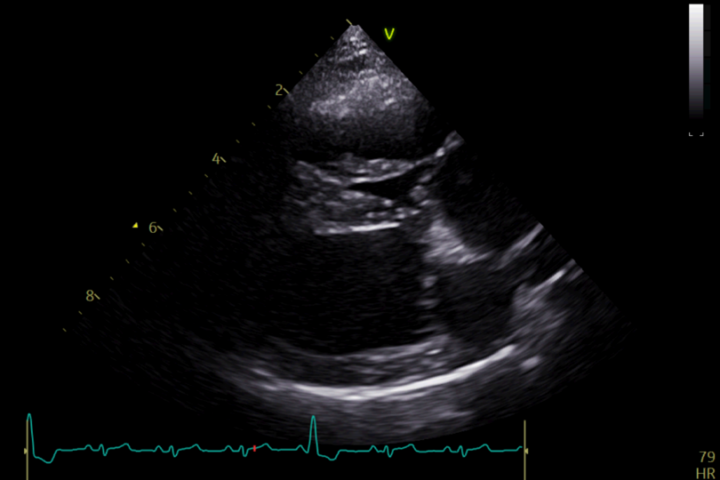

Echocardiographic findings

Echocardiography serves as the cornerstone for diagnosing and characterising PS (Figure 1). Typical echocardiographic findings include thickening and reduced mobility of the pulmonary valve leaflets for valvular stenosis. In mixed-type presentations, narrowing of the pulmonary valve annulus or pre/supravalvular obstructions, consisting of fibrotic tissue, are common. Post-stenotic dilation of the pulmonary artery is common due to the faster flow across the valve region. Doppler interrogation allows for the quantification of the PG across the stenotic segment, aiding in disease severity assessment.

Secondary changes include reduced right systolic function, right ventricular hypertrophy and right atrial enlargement with/without tricuspid regurgitation. Signs of right-sided congestive heart failure (CHF) include ascites and pleural or pericardial effusion.

Medical or surgical therapy

Medical management aims to alleviate clinical signs (ie collapse, exercise intolerance) and improve quality of life. Beta-adrenergic blockers, such as atenolol, are commonly prescribed to reduce heart rate and myocardial oxygen demand. These must be gradually introduced and never stopped suddenly. Diuretics may be indicated for managing signs of right-sided heart failure. However, medical therapy alone is often insufficient for addressing severe cases of PS, and the disease tends to progress without a surgical resolution.

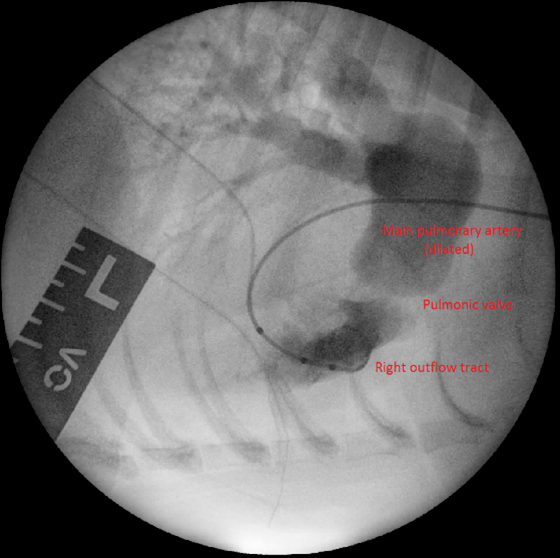

Surgical intervention is considered the treatment of choice for moderate to severe PS. Balloon valvuloplasty (BVP), a minimally invasive procedure, involves the insertion of a balloon catheter into the stenotic pulmonary valve and inflation to dilate the narrowed area (Figure 2). This technique has demonstrated excellent short- and long-term outcomes in dogs with valvular stenosis, with significant improvements in clinical signs and survival rates.

Complications of BVP include arrhythmias and haemorrhage. Moreover, some dogs might not fully respond to BVP with only a minor reduction in PS severity (reduction of 50 percent or more is considered successful).

In cases where BVP is unlikely to be successful (such as in cases with mixed-type PS), pulmonary artery stenting may be pursued. This is a minimally invasive technique that involves the implantation of a metal stent across the stenotic lesion (Borgeat et al., 2021). Complications for this procedure, besides those listed for BVP, include stent fracture, migration and crimping.

Open-heart surgery for right ventricular outflow tract grafting with an expanded polytetrafluoroethylene patch under cardiopulmonary bypass has been described as well (Bristow et al., 2018).

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with PS depends largely on the severity of the obstruction and the presence of concurrent cardiac abnormalities or heart failure:

- Dogs with mild to low-moderate PS may have minimal or no clinical signs and live a relatively normal life, although routine echocardiography is suggested

- Those with severe disease that have undergone successful surgical treatment have long-term survival rates that are generally favourable (Johnson et al., 2004). Ongoing monitoring and management are, however, essential to optimise outcomes

- Unfortunately, dogs with severe disease and no surgical correction have a guarded prognosis and they will likely develop right-sided CHF

Conclusion

PS represents a significant clinical entity in veterinary cardiology, requiring a comprehensive understanding of its pathophysiology, diagnostic evaluation and therapeutic options. By recognising the clinical signs, interpreting diagnostic findings and implementing appropriate management strategies, veterinary surgeons can effectively manage canine patients with PS and improve their overall prognosis and quality of life (Francis et al., 2011).

Pulmonary stenosis represents a significant clinical entity in veterinary cardiology, requiring a comprehensive understanding of its pathophysiology, diagnostic evaluation and therapeutic options

Atrial septal defects

An atrial septal defect (ASD) is an abnormal communication between the right and left atria due to a defect in the interatrial septum. Typically, this leads to the redirection of blood flow from the left atrium into the right atrium and ventricle. However, in cases with concurrent right heart abnormalities, shunting may occur in a right-to-left direction.

Prevalence and predisposition

ASDs represent 1 to 2 percent of congenital heart defects in dogs and are, therefore, considered rare (Oliveira et al., 2011; Schrope, 2015). There is no obvious breed predisposition, but one paper showed that Boxers are commonly affected by ostium secundum ASD (Chetboul et al., 2006).

Pathophysiology

The embryological development of the atrial septum is complicated. It first involves the growth of a septum from the roof of the atria (septum primum), which then grows to meet the endocardial cushion. Failure to close completely causes an ostium primum ASD (a rare presentation). A gap in the dorsal part of the septum primum is, instead, called ostium secundum ASD. Beside the septum primum, another septum (septum secundum) will grow parallel to the first, leaving a small fenestration open towards the atrioventricular region, called the foramen ovale, which is used to shunt blood from right to left in foetal life. In foetal life, the blood goes from the right atrium, across the foramen ovale, through the septum secundum and into the left atrium. After birth, both openings should close.

Other types of atrial septal defects include sinus venosus defects (abnormal attachments of the right pulmonary veins to the vena cava) and coronary sinus defects (failure to close the wall between the coronary sinus and the left atrium).

Atrial septal defects normally lead to right volume overload due to blood shunting from the left atrium to the right atrium. This is due to higher right ventricular compliance

Atrial septal defects normally lead to right volume overload due to blood shunting from the left atrium to the right atrium. This is due to higher right ventricular compliance.

Clinical signs

Most of the time, dogs with ASDs are asymptomatic, at least until they are three to five years of age (Buchanan, 1999). The presence of a murmur might be detected when a large ASD is present; in these cases, the heart murmur is due to relative pulmonic stenosis (increased pulmonary flow due to right volume overload) and not as a result of blood flow across the PDA. Clinical signs might be consistent with right-sided CHF.

Diagnostic evaluation

Thoracic radiographs might show right-sided cardiac enlargement, but the most reliable diagnostic tool is echocardiography.

Echocardiographic findings

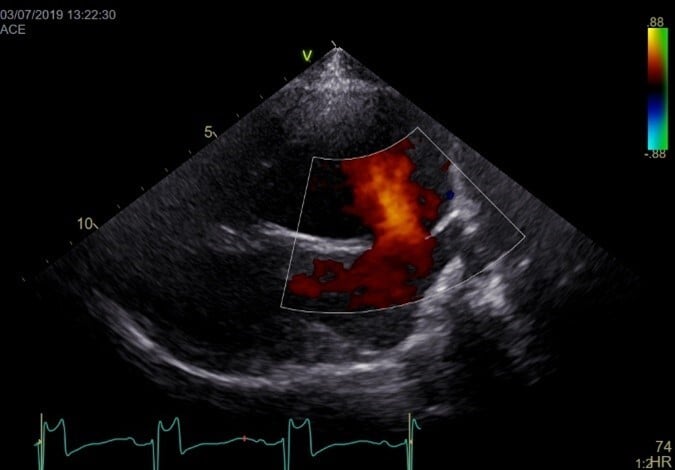

Echocardiography shows an anechoic portion of the atrial septum through which colour Doppler might demonstrate blood flow (Figure 3).

The location of the defect depends on the type of ASD. Ostium secundum ASD is the most common and is localised in the dorsal region of the septum. Flows across the defect are often laminar (not turbulent; normal velocities). Often, an artefactual echo dropout at the level of the atrial septum can mimic an ASD in two-dimensional echocardiography. A patent foramen ovale can also result in blood shunting; however, a membrane is usually visible (no anechoic region).

A bubble study can show if there is right-to-left shunting with direct visualisation of bubbles going from the right to the left atrium.

Medical or surgical therapy

Unless there are signs of right-sided CHF, medical therapy is not required. Surgical occlusion of the defect can be considered, especially if the defect is large and causes clinical signs. This can be done with a minimally invasive approach using devices such as an Amplatzer atrial septal occluder (Gordon et al., 2009) (Figure 4).

Prognosis

There is limited literature regarding survival time of dogs with ASD. Dogs with small ASDs usually have a good prognosis. However, those with clinical signs and CHF will have a limited life expectancy as with other conditions that cause CHF.

Conclusions

In summary, the most common ASD is ostium secundum. These defects usually lead to right-sided volume overload. If small, ASDs may remain asymptomatic; if large, they can induce right-sided overload and CHF. Being confident with the various types of ASD, as well as artefacts that can mimic this condition, is important to prompt the correct approach for these patients.

| More congenital heart defects in dogs are covered in the second article in our series. |

_OL_CourseThumb.jpg?width=500&height=300&name=IVE_GPCert(Cardio)_OL_CourseThumb.jpg)

Cardiology

ISVPS General Practitioner Certificate (GPCert)

HAU Postgraduate Certificate (PgC)

References (click to expand)

After graduating in 2015 from Italy, Mattia completed internships at the University of Liverpool and Lumbry Park Veterinary Specialists before working in a busy first opinion hospital in Hampshire. During this period, he completed a certificate in cardiology (CertAVP VC). In March 2022, Mattia became a boarded cardiologist at the European College of Veterinary Internal Medicine – Cardiology, and he joined ChesterGates Veterinary Specialists in April 2022. He also completed an MSc program in veterinary professional studies in July 2023. Mattia likes all aspects of veterinary cardiology with a particular interest in congenital diseases and interventional cardiology. Mattia is a co-founder of VetSpoke, a project that aims to bring veterinary specialists closer to vets and pet owners across Europe.